Frozen shoulder—also known as adhesive capsulitis—is a common, painful, frustrating, and often misunderstood condition. It is a very common cause of severe, debilitating shoulder pain in adults. And given its association with metabolic conditions such as diabetes and insulin resistance, its prevalence is increasing.

It’s especially prevalent in midlife, in perimenopausal women, and in people with metabolic issues like diabetes. It can be very painful, limit motion for months, and can be misdiagnosed and mistreated as a rotator cuff issue far too often.

Let’s unpack it.

The presentation is usually classic. You woke up one day and noticed severe shoulder pain. You do not recall any injury. Perhaps you recall an innocuous strain in the gym a few weeks ago, had a flu vaccine, or, like most, don’t remember anything that could be related.

The pain intensifies, often making it hard to use the arm for most normal activities of daily living. Sleeping becomes a significant challenge.

Statistically speaking, you are likely to be between 40 and 60 years old, female, and peri- or postmenopausal. A frozen shoulder can occur in men, too. It’s far less frequent, unless you have insulin resistance or diabetes.

As I have said in many of my posts. Joint pains and many joint issues are a frequent manifestation of metabolic dysfunction. Our joint structures are just as susceptible to changes from inflammatory mediators from chronic disease as the heart, brain, kidney, and liver are.

Prevalence and Risk of a Frozen Shoulder

Roughly 2–5% of the general population will experience frozen shoulder in their lifetime. But among certain groups, that number jumps dramatically:

In people with diabetes, up to 20%

In women in their 40s to 60s, it is 3 to 4 times more common than in men

In perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, the risk increases sharply

We don’t fully understand why, but we have some clues, especially from metabolic and hormonal perspectives.

The Natural History of a Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder often begins without trauma. It may follow an innocuous shoulder strain, an injection, or even a seemingly minor tweak—something you'd usually ignore. Then, over days to weeks:

Pain phase (Freezing): Pain, especially at night, often has an abrupt onset. This pain can be intense. There is pain moving in most directions, and there is often severe pain at night. Motion might still be normal at this stage. This is the most crucial stage for recognizing and treating this condition.

Stiffness phase (Frozen): Pain may plateau; it’s not gone, but it’s better. But now motion is limited. You can’t reach up your back as far as you could, and you can’t reach the top shelf of the cabinet. Putting on a coat or jacket can be a problem.

Recovery phase (Thawing): During this last phase, the shoulder is recovering. The inflammation has resolved, but the stiffness remains and is slowly improving. Depending on several variables, this stage can last anywhere from 6 to 12 months or longer.

Untreated, the entire process can take 1 to 2 years, and sometimes longer. Fortunately, many people improve without surgery, but it’s not a benign condition: it disrupts sleep, daily function, and quality of life.

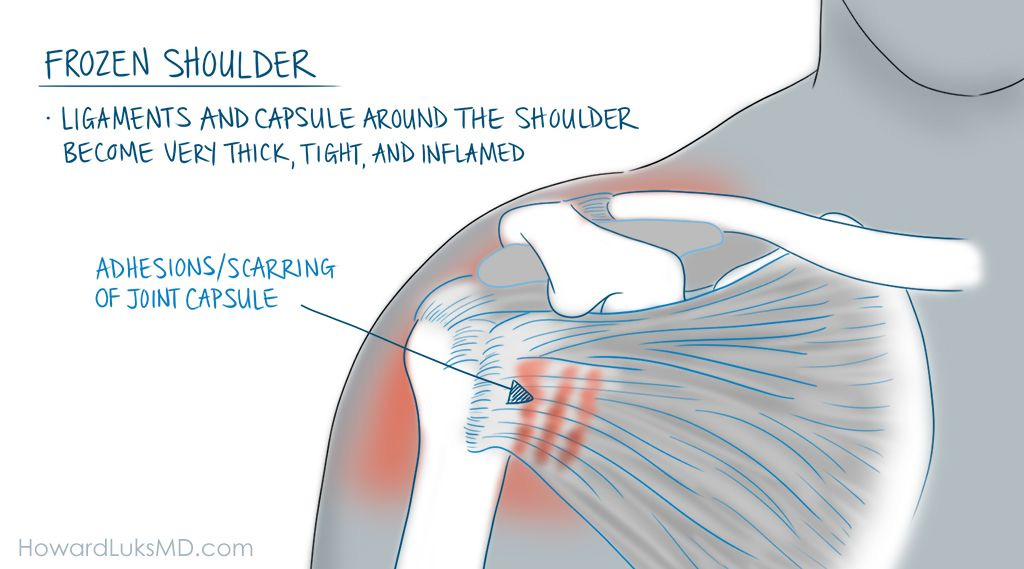

Pathophysiology: A Joint That Closes In

The bones of our shoulder joint are surrounded and held together by a thin, flexible capsule. That capsule also has ligaments in it, so our joint doesn’t dislocate. In frozen shoulder, the capsule becomes inflamed, thickened, and contracted. Adhesions form. The joint volume literally shrinks.

Have you ever seen a recreational boat pulled from the sea and stored for the winter? They shrink wrap a white plastic around it. That’s what happens to your shoulder capsule.. except that it’s red and inflamed, too.

This isn’t a tendon issue. It’s not your rotator cuff. It’s a capsular contracture, often with some inflammation but without the findings you’d expect in more mechanical shoulder injuries, like tears of the cuff, etc.

That’s why treatment—and diagnosis—needs to follow a different path.

Diabetes and Frozen Shoulder: Why It Hits Harder

People with type 1 and type 2 diabetes experience a more severe, prolonged, and recalcitrant course. Why?

Collagen glycation: Chronic high blood sugar leads to advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which attach to collagen and cause stiffening of connective tissue, including joint capsules.

Microvascular changes: Small-vessel disease limits healing and contributes to chronic inflammation.

High levels of inflammatory mediators associated with metabolic disease leave us susceptible to a frozen shoulder.

Why Perimenopausal Women?

This is one of the most common groups affected, and again, we’re learning more about why:

Hormonal shifts: Estrogen influences connective tissue turnover, collagen structure, and inflammation. Its rapid decline during perimenopause may disrupt the homeostasis of joint capsules.

Changes in metabolic health: Midlife often brings subtle metabolic dysregulation, including insulin resistance, even in thin, active women.

Sleep disruption: This population is already at risk for poor sleep, and frozen shoulder pain at night exacerbates this condition, further worsening central pain sensitization.

Often Misdiagnosed, Often Over-Treated

Here’s a frequent mistake:

A patient develops sudden, severe shoulder pain with no trauma. They have a cursory exam. Key clues are missed. They’re sent for an MRI. The MRI shows a partial rotator cuff tear, labral fraying, or age-appropriate tendinosis.

And now they’re booked for surgery. Or they are sent for the requisite 4 weeks of physical therapy, which doesn’t work because it takes a lot longer to work in a frozen shoulder. Now the patient is offered surgery because the wrong structure is blamed for the pain.

But here’s the catch: an early frozen shoulder can present with severe pain before stiffness occurs; thus, range of motion can be normal at first. If you’re not examined carefully—especially looking for loss of motion—you might miss it.

People with severe shoulder pain need serial examinations. Because motion may be normal very early in the disease course, but it will not be normal a few weeks later.

Surgery in the setting of a frozen shoulder often leads to worsening stiffness, more pain, and regret.

Key clinical clue: If someone experiences night pain, sudden onset, and progressive loss of motion, consider frozen shoulder as the initial diagnosis, rather than a rotator cuff injury.

Treatment: Mostly Conservative

1. Education and reassurance

This condition improves. It takes time. People need to hear that.

2. Physical therapy

Gentle range-of-motion work—not aggressive stretching early on—can preserve motion and reduce disability. During the highly inflammatory stage, pushing and stretching too hard can lead to an inflammatory viscous cycle. At the bottom, I will show you some stretches to do a few times a day on your own.

3. Steroid or Hydrodilation injections

These can significantly reduce pain, especially in the early (freezing) phase. Injecting the shoulder joint can make a significant difference in cases of frozen shoulder. First, it limits the inflammation; second, if the stiffness from the capsule becoming thicker hasn’t started yet, the shoulder range of motion will improve rapidly. We perform two types of injections. One is a hydrodilation, where we inject saline and a steroid. This is intended to help stretch or dilate the capsule. The second is a straightforward steroid injection to address the inflammation. Both of these injections, if placed early in the disease course, before the capsule becomes thickened, are very effective.

4. Oral anti-inflammatories

Short courses may help reduce pain, but are far less effective than injections.

5. Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) or arthroscopic capsular release

Reserved for patients with prolonged, severe stiffness who have failed conservative care over many months. In these instances, we sedate you and move your shoulder for you to break up the thickened capsule. Sometimes we will place a camera in the shoulder with another device to cut the thickened capsule.

Most people with a frozen shoulder are afraid to move it. That’s a natural inclination. But the best thing to do is to start stretching, within reason, as soon as possible. Even light-weight lifting can be beneficial in improving motion. If you're capable of counter-top push-ups or standard push-ups, they will help improve your motion, even if the shoulder motion and the distance you can move are limited.

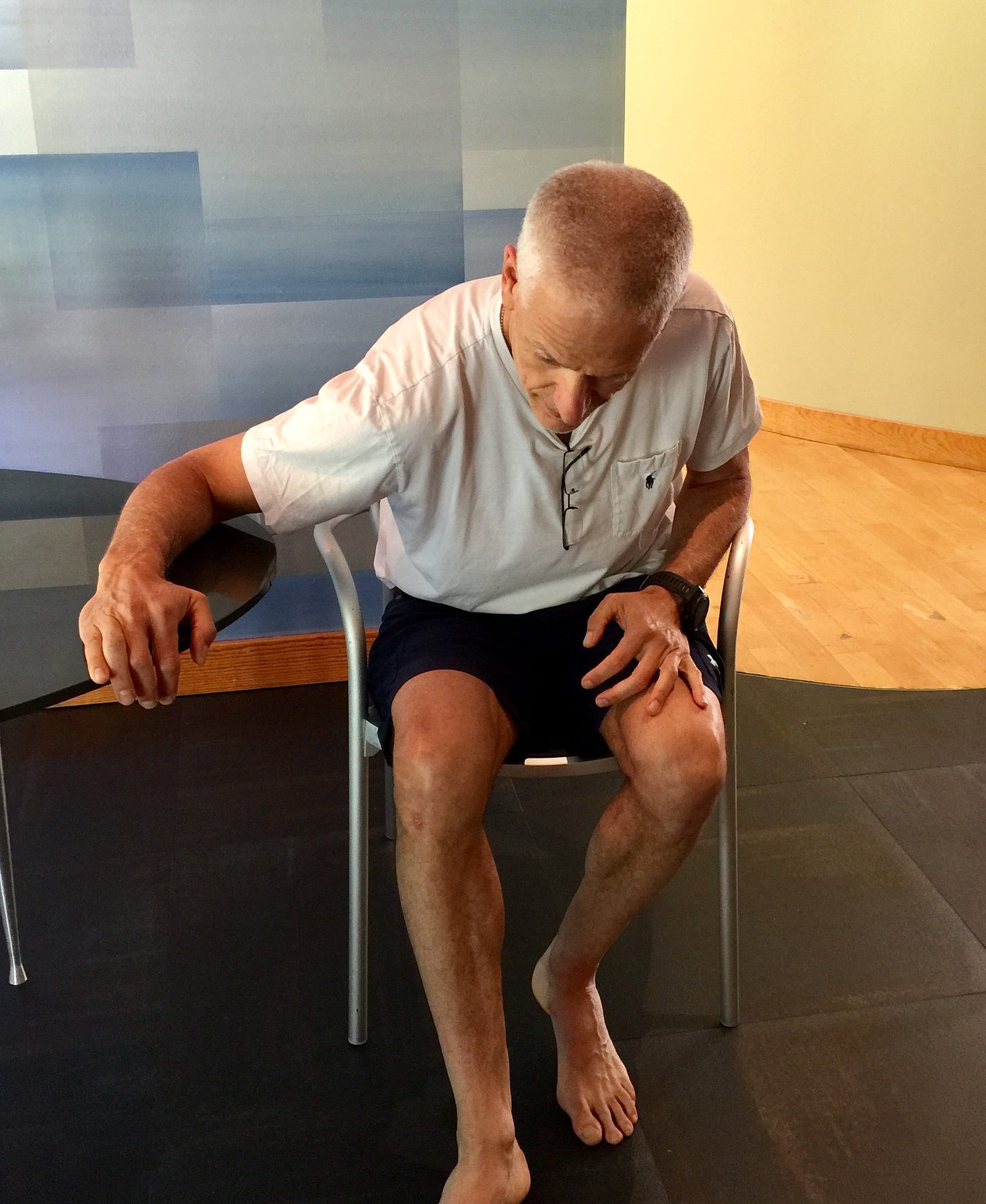

Put your arm on the table with your elbow bent ~ 90 degrees. Try to lean forward gently. Hold that for a count of 3-5 seconds, then relax, and repeat it 10 times. You can also twist your torso in the opposite direction towards your arm on your lap.

Put your arm on the table straight out in front of you. Try to bend forward at the waist. When you reach your maximum, hold that position for 3-5 seconds, then sit up, relax, and repeat the process 10 times.

Place your arm against the wall or a doorpost. Your elbow can be bent to varying degrees. Meaning that you can do this with your elbow bent a little, or bent around 90 degrees. When you adjust the bend of your elbow, you will focus the stretch on different regions.

Once you are set, now turn your body in the opposite direction. Do this gently. Hold the position for 3-5 seconds, relax, and then repeat the process 10 times.

You can also reach up on the wall or door as far as you can and try to step forward. Again, hold that position for 3-5 seconds.

Frozen shoulder is common. It’s painful. It’s treatable—but often misunderstood. Getting the diagnosis right prevents overtreatment and limits the suffering. Providing patients with clear expectations and timeframes reduces anxiety.

Serial examinations and careful reflection can prevent delaying treatment and result in rapid improvement. Seek treatment earlier rather than later, since early intervention will dramatically decrease the timeframe of suffering and disability.

I do notice a lot more how so many folks with metabolic issues even if they think they are managing it have a hard time understanding how diet, very low activity is often a primary or strong secondary component in joint/fascia issues. When you suggest a reasonably brisk walk most days they will say they walk at work but that is task specific just like driving in bump and grind rush hour traffic isn't an enjoyable/relaxing drive. All too often they want to be "fixed"but don't get the idea of doing somewhat simple consistent activity. I always say to them that they need to walk without phones, leashes and strollers in the hands as the natural counter rotation is one of the most valuable components of walking/running.